文 TEXT // 曲一箴 Twist QU、何颖雅 Elaine W. HO、Michael EDDY、植村 絵美 UEMURA Emi、刘颖 Dongdong LIU Ying

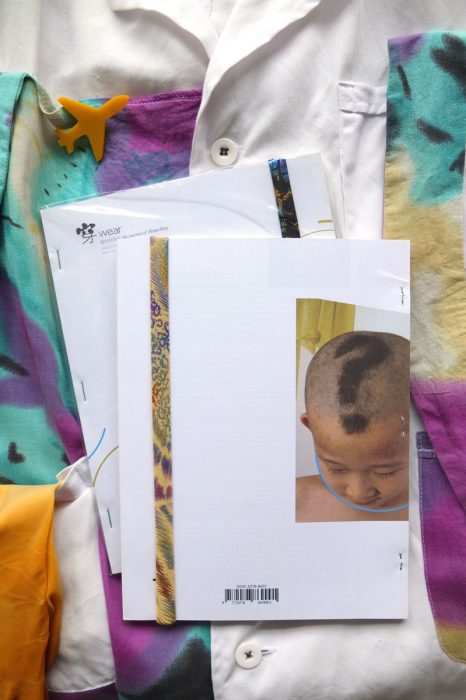

家作坊小经厂胡同空间 HomeShop at Xiaojingchang Hutong,2018-2010年(摄影 PHOTO:高伟云 Jeroen de KLOET)

关于这个2018年十二月的到来已经存在很多讨论,认为它纯粹是四十年前那场洪流开闸的一个象征。四十年的开放,一直不间断的变革,使得我们——至少是我们当中年下四十者——并不真的知道“如果不这样,会是什么样?” 纪念日,成了对我们“一直以来都知道”的现状的庆祝。不过生日、周年庆不就是希望事情都如此进行下去、庆祝我们自己以及“事物现有的样子”吗?不是扫大家兴——啊大好盛世万岁万岁——实话说,庆祝现状还是有些令人悲哀沮丧的,即使或者说尤其这现状发展如此不均衡,不间断的转换一切发生的那么快,我们的灵魂都要跟不上了。¹

There has been a lot of talk about the arrival of this December 2018, a purely symbolic commencement of that which was real and like a wildly burst floodgate forty years ago. Forty years now of opening and ongoing change that many of us, at least those of us under forty, don’t really know otherwise, so the anniversary becomes a celebration of a state of existence that we’ve always known. Indeed, are not birthdays and anniversaries merely a wish for things to continue, a celebration of ourselves and ‘the way things are’? Not to be a party pooper—long life and all that hoo hah are great and everything—but to be honest, there is something pathetic and disturbing about the commemoration of the status quo, even if—and perhaps especially if—that status quo is uneven development and constant transition happening so fast that our spirits are unable to keep up.¹

得承认,为这个特殊的纪念日写点什么于我们而言有点难度。写作,正是这个纪念日所蕴含的精神之一,但我们的精神却没跟上。没有跟上改革开放,也没有跟上另一个——比人人都在讨论的这个规模小一些的,情况。

So yes, this particular anniversary is something difficult for us to write about. The act of writing is perhaps exactly an exercise of the spirit, and our spirits have still not caught up. With Opening Up and Reform, but actually also to another, slightly smaller occasion than the one that everyone is talking about.

空间门口的黑板每天更新的PM 2.5天气预报,查看纪录在家作坊的微博:@jiazuofang

Daily PM 2.5 weather reports posted outside HomeShop and on the HomeShop Weibo account @jiazuofang

五年前的2013年12月31日,是北京名为“家作坊”的独立艺术空间最后一天运营的日子。家作坊存在了五年半,这意味着2018年是它的第十年。五年、十年、四十年,在这些数字之间我们交替庆祝开、关、开、关——宛若一颗鲜活的心脏在持续跳动。家作坊关闭差不多两年后,艺术家、作家张小船和何颖雅其实共同创作过一篇云文本围绕爱与家作坊,英文题目即为“On the Ongoing Labours of Love: HomeShop Opens and Closes, Opens and Closes(直译:“爱的持续劳动:家作坊的开、关,开、关”)”。² 中文题目稍有不同:“心瓣运动请继续:谈一场集体的恋爱”,戏谑地将恋爱的劳动问题提取出来,以促进对爱的社会性的进一步思考。当然,这爱与劳动这二者都值得探讨,尤其是当我们回到关于周年与纪念的思考上时,也许可以进一步反思劳动、爱、与社会之间的关系。仪式,诸如婚礼、开业典礼、宣布经济改革,就是在日常基础上将组织着我们私人生活的各项活动变得明确、公开、社会化。两个人之间的爱情,从某种意义上说确实与他们以外的世界毫无关联,但人们也认同婚姻意味着两个家庭之间缔结的合约,因此也反过来决定了个人与国家或国家服务之间的关系。如一位朋友所言,同性婚姻之所以重要,因为它决定了生死关头,你是否有权站在自己伴侣的身边——医院陪护权可是个法律问题。

December 31st, 2013, five years ago, was the last day of an independent art space in Beijing named HomeShop. It had existed for about five-and-a-half years, meaning that 2018 is also the ten-year anniversary of its opening, so between the fives and the tens and the forties we can alternately celebrate openings and closings, openings and closings—something like the beating of a pumping heart. Actually, almost two years after HomeShop’s closing, artist and writer Boat ZHANG and Elaine W. HO wrote a clouded text together about love and HomeShop, the English title of which was, “On the Ongoing Labours of Love: HomeShop Opens and Closes, Opens and Closes”.² The Chinese was named a bit differently: “心瓣运动请继续:谈一场集体的恋爱”, interestingly taking out the question of labour in relation to love in favour for a stronger consideration of the sociality of love. Both are valid, of course, and especially if we go back now to the consideration of anniversaries and commemorations, it may be possible to reflect upon these relations between work, love and society. What rituals such as weddings, opening parties and even the declaration of economic reform do is make explicit, public and social, the activities that organise our private lives on a daily basis. The love between two people may in certain senses seem to have nothing to do with the rest of the world, but most of us know that the act of marriage contextualises that love between two as an agreement between families, which in turn determines many other relations between individuals and the state or state-run services. As a friend explained, gay marriage is important exactly because of that right to be the one to accompany your partner into the hospital in times of need. Being there for someone is a question of legal admissibility.

那劳动跟我们探讨的有什么关系呢?说实话,现在这个时代什么不是工作?劳动支配着绝大多数人的生活。换个角度,如果你恋爱过,就应该知道这是多么特么辛苦的一种劳动。劳动涉及时间和价值,周年庆祝何尝不是?我们“致敬”我们创造出的价值、投入的心血——它可以是一场婚礼、一个艺术空间,又或是一项国家政策。因此文章题目“心瓣运动 Opens and Closes, Opens and Closes”非常贴切我们的情况, 因为我们针对的就是这一一个持续不断的过程,劳动的过程,而并非“婚姻”或者极权政党的“统治”——自身又是结果又是目标。

And then labour, what does that have to do with anything here? Well, what isn’t about work these days, especially when labour governs most of our lives? Or in another sense, if you’ve ever loved, then you know it is a fucking lot of work. The question of labour has to do with time and value, just like an anniversary celebration. We ‘pay tribute’ to the value we’ve created by spending our time on something, be it a marriage, an art space, or a national agenda. So it’s fitting in our case that the text was titled “心瓣运动 Opens and Closes, Opens and Closes”, because what we are referring to—and why the question of labour is important—are on-going processes rather than marriage in and of itself as a goal, rather than totalitarian party domination in and of itself as a goal.

所以即使过去了五年、十年(这会儿关着还是开着,取决于你是个悲观主义者还是乐观主义者)我们依然感慨万千,讨论着这个我们倾注了无数心血、时间和精力的空间,关键在于要将其置于更广泛的一种语境下去理解:艺术家运营的空间倾向于无法生存下来;介入社会、激进分子的实践会耗损(或压制)个人精神;对衡量成功与失败方法的重新审视变成一种需要。在柏林的“空间实验研究所”,奥拉维尔·埃利亚松(Olafur Eliasson),一位从任何传统意义上讲都极其成功的艺术家曾对我们说:“如何衡量你们已经取得的成功?”戏剧化的停顿之后,“取决于看你们将要去哪儿”。虽然听起来这是对反思的一种启发式呼吁,但某种程度上仍是一种说教:提出一个值得思考的问题然后替你做出回答。而且,当我们将埃利亚松的这番话与社会中公认的、有威望的成功人士的发家事迹并列起来做分析的话,就会发现一些蹊跷。以政府腐败为例,所有犯事的领导都在向我们展示,被捕前染指肮脏的勾当如何助他们平步青云。当然,贪官得以绳之以法,被公开羞辱,习发起的这项运动大快人心,这是后话,但埃利亚松式并置“过去-未来”的思考方式,重视目的与结果,却忽略了每个当下的劳动、日常实践与道德规范中持续不间断的心跳,我们认为,是这心跳让我们理解自己在工作、爱与社会中的位置。

So even if five or ten years later (closing or opening, depending upon whether you’re a pessimist or an optimist), we are still emotional and talking about a space that we invested so much of our time, hearts and energy into, it is crucial to contextualise it within a broader sphere of understanding: artist-run spaces that have a tendency not to survive; socially-engaged and activist practices that wear down (or clamp down upon) individual spirit; the need to re-evaluate measures of success or failure. At the Institute for Spatial Experiments in Berlin, the by all traditional measures extremely successful artist Olafur Eliasson once said to us, “How do you measure the success of what you’ve done?” after which he paused dramatically then answered, “By where you’re going”. Despite the inspiring appeal of this lesson, there is a certain degree of didacticness of someone who asks thoughtful questions and then answers them for you. Thinking a bit further, there is something additionally problematic if we analyse Eliasson’s statement in juxtaposition with the track records of many people in society who are deemed powerful and successful. Corruption in government, for example, reveals that for all those leaders before they get caught, doing dirty shit gets you pretty damned far. Of course the getting caught and publicly shamed part of it is the kind of justice that lends Xi’s campaign its popular appeal, but it is exactly that the past-future juxtaposition of Eliasson’s statement neglects the on-going heart pump of labour, daily practice and ethics that is the core of understanding our positions within the schema of work, love and society.

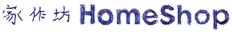

家作坊明信片 HomeShop postcard,2010年(摄影 PHOTO:何颖雅 Elaine W. HO)

所以再一次我们感到,“家作坊曾经是什么、现在是什么、对我们意味着什么”,很难被压缩打包。回顾最初,家作坊开幕时印刷了一批明信片,算是空间第一批免费领取的纪念品也是空间的名片:明信片正面留出了一个照片区域,灵感来自于北京随处可见的流动工人,他们往往闲散地站在街头,脚边立一块板子,上面简单地用手写下可以干的活儿算是广告。岌岌可危的工人身份和乞丐并置的刺激性视效与我们产生了某种共鸣。作为独立艺术家(无画廊)和/或自由撰稿人(无“单位”的设计师、翻译、教师),我们拟出了自己的广告,请欧阳和Michael作为模特在纸板前摆出各种造型,纸板上列举了所有我们作为一个联合团体和具备一些资源的空间所能提供的各式服务。也许这种“低级”并没有让我们在潜在的客户、消费者或者观众面前表现的足够有吸引力,但如果在艺术的语境下这意味着什么呢——我们就是可供低价雇佣的艺术家吗?事实上,用“雇佣”来形容被画廊签约的艺术家也不过分。大家心知肚明的是,市场友好型的艺术家往往采取一种策略,将自己的作品分入两股阵营——一个是“直抒胸臆”型,不可能卖出去,但更直接的表达了他她本人或是他她的品牌;另一个,则是“收藏友好”型,考虑收藏家所需陈列的各种墙壁或场景划定不同的价格和形式。如果将家作坊的作品与之同框比较(以当初的明信片为证),我们现在回头来看,当时所采用的策略就“是”提供低价可雇的艺术家,但我们带来的各异“胸臆”、无边脑洞困惑震惊了所有的人:艺术品、行为、音乐、遛狗、复印、送外卖。现在空间已不复存在,而我们也许终于可以拨开一丝云雾:将共享一缸资源的各类劳动视为平等是出于“工作”本身的考虑,而艺术家和收藏家、设计师和客户、表演者和观众之间的关系,则是“作品”。³ 这实际也是对自组生活这种形式更大规模的反思和实验,于我们而言,也是为工作、爱、社会提供了一种替换性图解。或者干脆让我们称之为“scheming密谋”而非“schematic图解”,让我们回到艺术。在英语中“scheme”来自于希腊语“skhēma”,意为“形式”或“图形”,所以家作坊的隐性scheme可能是试图去找到、或创造生活中的艺术性出来,用以表达还不为人知的关于工作、爱、社会的图形结构。

So again, that is why it’s difficult to encapsulate what HomeShop is or was, and what it has meant to us. There are just so many moments…so, so, so many moments. And maybe it was always HomeShop’s modus operandi to try to avoid inasmuch as possible being encapsulated, neatly categorised or appropriated. Did that lead to our own demise? Perhaps.

Looking back to the very beginning, it was part of HomeShop’s opening that we printed a set of postcards to serve as a kind of first free souvenir and calling card for the space. The image on the front was prepared as a photo session inspired by itinerant workers who used to often be seen around Beijing, standing idly with a simple handwritten cardboard sign at their feet advertising their services. This poignant visual juxtaposition between the precarious labourer and the beggar was something that resonated with us, all working as independent artists (no gallery) and/or freelance workers (no danwei designers, translators, and educators). So following their lead, we organised our own version of advertising involving models Xiao and Michael in various configurations before a cardboard sign listing all the various services we were able to offer as a combined group of people and a space with a few resources. Maybe this ‘downgrade’ didn’t make us appealing enough to render us desirable to potential clients, customers or audiences. And what does that mean in the context of art—were we simply cheap artists for hire? Actually, ‘for hire’ isn’t such a distant calling, even for gallery-signed artists. It is a well understood strategy of market-friendly artists to divide their work into two strands—one of ‘pure output’ with no possibility of selling, yet which are more direct expressions of the artist and his or her brand—and the other, value-sized pieces which are friendly to the walls and other surfaces of collector’s homes. That perhaps puts the work of HomeShop in a framework for comparison, as the postcard attests to a strategy that we can now look back to in retrospect as—YES—cheap artists for hire, and yet with a range of outputs so diverse and mind baffling as to confuse everyone: artwork, performance and music, but also dog-walking, photocopying and meal delivery. But now that the space is long gone, maybe finally we can clear the cloud a bit: to equate the various forms of labour based upon a collective pooling of resources is a consideration of work itself—and the relations between artist and collector, designer and client or performer and audience as ‘the work’. This, then, is in fact a larger rumination and experiment with forms of self-organised life, which in our terms, is an alternative schematic for work, love and society. And let us rather call it a ‘scheming’ over the fixed delineations of the ‘schematic’—which brings us back to art. The word ‘scheme’ in English stems from the Greek skhēma, meaning ‘form’ or ‘figure’, so it would be that the hidden scheme of HomeShop was in fact an attempt to find form, or to create an artwork, of an as of yet unknown configuration between work, love and society.

绝大多数阅读本文的读者估计不会将家作坊2008年至2013年所栖居的两个朴素的空间与上文所提的雄心壮志联系在一起,就连身在其中的我们中很多人也不会。关于生命、哲学、政治、信仰的宏大问题与构成俗常生活的细小任务,二者的分裂才是“真现实”。是的,“真现实”就是如此巨大、开裂的一个口子(应景了“后真相”时代)。家作坊的日常调度包括所谓“核心成员”们组织管理空间及其活动,收/交月租,打扫卫生,做饭,在房顶种菜,学习,以及其它。如果这被看做是在努力寻找一种别样的生存方式,那它在对这场革命不断地轻声诉说:是合作,而非冲突,奠定了胜利的基础。

Most of you who read this text now will not necessarily be able to connect such ambitions with the modest two spaces which HomeShop inhabited from 2008-2013. Perhaps many of us involved would not be able to either. The disjuncture between grander questions of meaning in life, philosophy, politics or religion, and all the minute tasks that make up the banal reality of everyday life, is the ‘real reality’. Yes, ‘real reality’ is actually a huge, gaping hole (and also why the ‘post truth’ era makes so much sense at this moment in time). The daily mise en scène of HomeShop consisted of so-called ‘core members’ of the space organising the space and its activities, collecting/earning the monthly rent, cleaning up, cooking, rooftop farming, studying and other daily matters. If this was any kind of attempt to find an alternative way of being, it was a very, very subtle whisper to revolution founded on collaboration rather than conflict.

合作事无巨细。当然也都伴随着冲突。家作坊五年半的经历说明了这一点,无数的相遇、聚会、合作伴随着无数的敌对、争执和决裂说明了这一点。发声的多样性太过重要,以至于有时会牺牲掉观点的清晰。所以这次,作为周年纪念的一部分,我们选择闭嘴,并请一些其它的声音来为你们描述,为我们(悼念)庆祝。受邀为此系列写作的三位是:楊立才(老羊), 丹敏以及阿布,他们来自于完全不同的背景,介入家作坊的方式和频率也不尽相同。如果存在有“家作坊大家庭”的话,那他们都是其中一员。这个大家庭成员如此众多,所以再次,它无论如何没法被轻易打包总结。

Collaboration is myriad. And of course, in direct liaison with conflict. HomeShop’s five-and-a-half year existence represents that, and for as many encounters, gatherings and cooperations, there were also antagonisms, arguments, and ruptures. This multiplicity of voices is crucial, sometimes even at the expense of clarity. And this is why this time, as part of our anniversary commemoration, we should shut up now and invite a few other voices to help describe to you and celebrate (or mourn) HomeShop for us. The three writers that have been invited to write texts for this 《同时 Companion》4 series—YANG Licai (Lao Yang), Danmin and Abu—come from completely different backgrounds, and their means and degree of participation with HomeShop also differ. If there is such a thing as a “HomeShop family”, then they would each be part of it. It’s a big family with many members, and that means exactly that it can’t be easily packaged or summed up.

家作坊北二条空间 HomeShop at Jiaodaokou Beiertiao,2010-2013年(摄影 PHOTO:何颖雅 Elaine W. HO)

让我们重回埃利亚松的问题,一个现在已经被解散了家庭,它的本质是什么?又或者说,但对于一个已下台的党派,它的成员制度意味着什么呢?我们认为这是一项遗产:正是这种成员制度让家作坊的创始人们走上了非常不同的道路、四散于诸众地方,从北京到柏林、香港、蒙特利尔,以及美国俄勒冈的尤金。而且这其实并不意外。最后一期家作坊自出版的《穿》杂志主题叫“有种”,从字面上看,也许这就是我们一直在做的——播下缓慢的种子。这株植物小小的,很有趣。它的叶子有一些已经枯黄,一路生长,一路掉落,但它的根还充满生机,果实还尚未成熟。目前我们还没法告诉你们这果实会是什么滋味,因为这“庆祝”还没有结束,仍在“改革”,仍在“开放”!一起欢呼,家作坊万岁!

Going back then to Eliasson’s question from another angle, what is the nature of this family now when it has already disbanded? Or, what does membership in a party that has already stepped down mean? It’s a question of legacy, we suppose, something that has led the original organisers of HomeShop on very varied paths, dispersed in many different places from Beijing to Berlin, Hong Kong, Montréal and Eugene, Oregon. And this, of course, is not so much a surprise. The last issue of HomeShop’s self-published 《穿 wear》journal was themed “有种” (translated as ballsy, literally “to have seed”), and that is literally what we’ve done—to sow slow seeds. They are the seeds of a funny little plant, with some of its leaves having already dried and been shed along the way. But its roots are very much alive, and its fruits are still on the way. We can’t yet tell you exactly what these fruits will taste like, but that’s because the ‘party’ isn’t over yet. (One of our writers in this series is even a ‘party member’, guess which one!) Still ‘opening up’, still ‘reforming’! So long live HomeShop, cheers to that.

《穿》杂志第三期:“有种” wear journal number three: “BALLSY”,2012年 [Available for purchase via 展销场 Display Distribute]

¹ 如斯维特兰娜·博伊姆引用的德国浪漫主义者弗里德里希·施莱格尔所说的话,“历史上真正的问题是人类发展各元素之间的进程不均衡,尤其是智力的发展和道德的发展之间巨大的分歧。” As Svetlana Boym quotes German Romantic Friedrich Schlegel, “The real problem of history is the inequality of progress in the various elements of human development, in particular the great divergence in the degree of intellectual and ethical development.” 斯维特兰娜·博伊姆 BOYM, Svetlana, 《乡愁的未来 The Future of Nostalgia》 (纽约 New York: Basic Books) 2001年.

² 何穎雅 HO, Elaine W. and 张小船 ZHANG, Boat,“心瓣运动请继续:谈一场集体的恋爱 On the Ongoing Labours of Love: HomeShop Opens and Closes, Opens and Closes”,《藝術世界 Art World》第295期,2015年4月。

³ 原文中,“工作”和“作品”都用“work”表示。

4 This text and the three additional essays by invited contributors were initially commissioned by 《同时 Companion》magazine, an initiative of 黄边站 HB Station (广州 Guangzhou). Links will be provided as they are published:

- 阿布的“北京日记”,2018年12月31发布 / Abu’s “Beijing Diary”, posted 2018 December 31

- 杨立才的“塔锥/星球”, 2019年1月7日发布 / YANG Licai’s “Peak of the Pagoda and a Celestial Body”, posted 2019 January 7 around 17:00 and removed on the basis of complaints of inappropriate content about twenty minutes later

- 丹敏的“沾点艺术的边儿”,2019年1月14日发布 / Danmin’s “Dip into the Edges of Art”, posted 2019 January 14

- 在在的“游吟,我的真实之地”,2019年1月21日发布 / Brother 7’s “My True Place Among Roaming Songs”, posted 2019 January 21

时间 posted on: 23 December 2018 |

时间 posted on: 23 December 2018 |  发布者 author:

发布者 author:

分类 filed under:

分类 filed under:

January 7th, 2019 - 21:33

[…] of 黄边站 HB Station (广州 Guangzhou). The introductory editorial by HomeShop can be read here, with additional links to be added as they are published […]