“In defence of… Gentrification”

By Igor Rogelja

My first doubts and concerns over how the term gentrification is used didn’t arise so much from a discussion on the applicability of the term in different socio-economic contexts. Neither were they stoked by the oft-cited misuse of the term by social observers, or by a desire to go against the grain of critical urban geography’s canon of work. While these are all issues I’ve worked with, the first time I actually, physically, flinched was when a city official from Kaohsiung, a Taiwanese port city, used the term in an overwhelmingly positive way, leaving no doubt that such a spatial restructuring was desirable: gentrification as a tool for development. There are of course several possible explanations – maybe the term was simply misused. Perhaps it is a rare and naïve display of candour that city bigwigs in most Western cities have long since learned to avoid, using instead either vacuous terms produced by PR departments or hiding behind complicated urban planning argot. Or both.

And yet, the notion of gentrification as a function of urban development opens new insights into the ways in which cities (especially in rapidly industrializing and developing countries) are being altered, with municipalities increasingly mimicking the input required to set off a gentrifying chain of event which, presumably, result in pleasant streets populated by attractive coffee-drinking people. In a manner that is both real estate-driven and top-down (and thus markedly different from real estate-led gentrification in New York, or the gentrification ground-zero of London’s Islington, where Ruth Glass first coined the term), it is as much a modernist state project, as well as a distinctly free-market driven process. Within the tension between these two loaded terms, project vs. process, I however see no inherent contradiction. Indeed, one finds an analogous shift within the mode of governmentality1 of the contemporary state, where broad societal visions (the project) are being complemented by a web of communities, stakeholders and interests, often reinterpreting the work of the state into a facilitator of personal (and corporate) aspiration, i.e. facilitating the process. Within this new city, whether we call it neoliberal or late-capitalist, gentrification has come to be seen as a central process (or culprit) by which spatial restructuring takes place and by which dilapidated housing stock is replaced, rejuvenated or otherwise shifts from the poor to the aspirational – often with at least the tacit support of the planning authority. Detected all over the globe and discussed in different academic fields, it is no surprise the term is both over-used (spurring Loretta Lees (2003) to upgrade it to ‘super-gentrification’), as well as maligned for its lack of clarity and tendency to obfuscate other important issues – a case which Julie Ren makes in a previous post about Beijing on this blog.

If we however suppose that the radical spatial restructuring in Asian cities is ‘something else,’ especially in the time since the idea of the creative city travelled there via epistemic networks in the late ’90s and 2000s, this requires a back to basics approach. My intention is to try to vindicate the use of the term even in contexts as varied as Beijing, Bangkok or Kaohsiung by looking at gentrification as a function of a late-capitalist spatial restructuring, especially when symbolic capital (Ren Xuefei, 2011) is taken into consideration and the producers of the symbolic meaning, Florida’s ‘creative class,’ become important actors in the field. What this means in practice is that gentrification by culture has become the dominant trend in Greater China, though it can be broken down further to identify both state, commercial and independent actors. Whereas ‘galleries, cafés and artists’ was a well-known gentrification cocktail in the West, these are now joined by an entrepreneurial state, advised by an epistemic community of planners and businessmen, and often following pre-existing templates. While examples ranging from Beijing’s hutong chic to Shanghai’s Xintiandi have been variously termed as commercialization, preservation, adaptive re-use and gentrification, they have in common a transition from being a place of local (and often marginal) meaning to (replicable) places of consumption and source of pride for the city authorities. Such also, is an example of Kaohsiung’s Park Road, once a messy stretch of hardware shops which has recently been redeveloped, as the jargon goes, into an artsy park as part of a city-wide effort to catch the creativity bandwagon.

Formerly, the area was known as Hardware Street (Wujinjie) and was very much a proxy for the city’s economic history – Taiwan’s dirty, sweaty port city where ships were disassembled, sugar exported and naphtha cracked. It is also a uniquely diverse city, as the rapid industrialisation pulled in large numbers of rural workers into the city – unusual for Taiwan’s otherwise rather tame rural migration. Since the late 1990s however, and for reasons deeply connected to Taiwan’s two party system (Kaohsiung is traditionally the bastion of the pro-independence Democratic Progressive Party), the city has embarked on an ambitious plan to rebrand itself from cultural desert to cultural hub. In itself, this is nothing remarkable; Manchester, Liverpool, Bilbao, Detroit have all had such turns in urban policy, successful or not. Rather, what is of interest in this case is the micro-level to which the city was engaged in the project of beautification and revitalization of the ailing blue-collar neighbourhood through which Hardware Street cuts. With its cluttered shop floors, oil slicks and loud noise of clunking metal, the street had been earmarked for ‘beautification’ in the run up to the World Games in 2009 in order to create a tourist corridor towards the Pier-2 Art Centre (a reused set of warehouses housing a municipal modern art complex) and to complete a bicycle lane network across the Yancheng neighbourhood (another strategy to attract the ‘creative class’). The demolition was divided in four stages, with the first one beginning in 2007 and the last one completed in 2011. Though the land is publicly owned and a park had been loosely envisaged in the area for decades, the issue here is not so much of legality – in any case the Taiwanese 1998 Urban Renewal Act grants municipal authorities ample powers to reconstruct urban areas, especially on publicly owned land.

Rather, the motivation for the decision is the key to understanding the way in which a gentrified ‘creative Kaohsiung’ is being constructed, not only as a physical space, but also as a space of identity and a new authenticity for Kaohsiung – a city of industrial heritage and a creative future. In this case, the radical restructuring of the abstract space of the plan caused the demolition of over 400 shops and adjacent living quarters and the forced historicization of what was very much a living industry. Thus, shops selling and repairing machine parts were replaced by public art and street furniture constructed out of the very parts which were the hardware shops’ livelihood, commissioned by the municipality and produced by local artists, many of whom have been intimately involved with the setting up of the nearby art centre as well. The area is now a showcase of Kaohsiung’s authenticity, its gritty industrial character now cleaned up for public consumption.

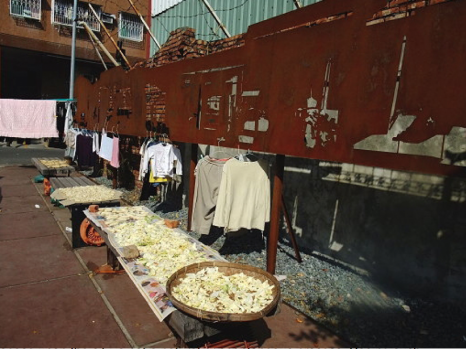

Faced with questions of identity and the allocation of space, the ‘authenticity’ of the area fragmented, as Sharon Zukin has shown on the case of New York’s gentrifying neighbourhoods (2010). In this case, the lived authenticity of the chaotic metalworking shops and the illegible network of unmapped lanes and gaps in the organically (illegally) grown neighbourhood is substituted by a planned authenticity of a different kind – in itself an important trait of gentrification. The industrial character of the area is translated through the instrument of public art into a dizzying array of street furniture and installations, all of which explicitly reference the history of the area – the irony is not lost on the remaining shopkeepers: ‘They took the things that kept us alive and made them dead,’ noted Mr. Bai, a hardware shop owner, while an elderly resident took things one step further, calling the park a place for dogs to shit where rich people can jog around, adding she has no time for such leisurely activities.

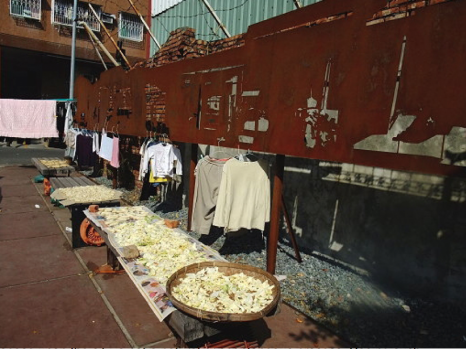

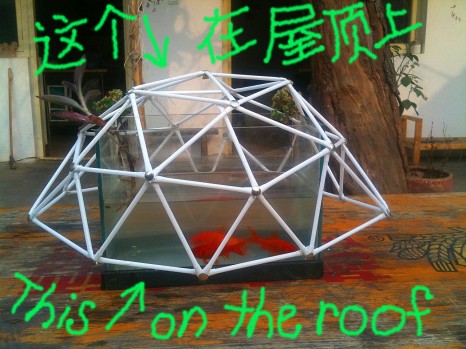

Though not explicitly expressed in city planning documents, the notion of authenticity is crucial to this neighbourhood from an economic standpoint and explains the effort to gentrify the area, rather than raze it completely or simply build a new part of town. Not only is the city government promoting mass tourism in the area, but a planned creative industry park also relies on the area’s authenticity to attract investment – most recently a large Hollywood digital effect firm. The firm, Rhythm&Hues, was initially being groomed by the municipal economic development office to occupy a suburban software industry park, but decided to base itself in an old warehouse instead, embracing the industrial feel of the building, which was inaugurated by Ang Lee in November 2012. The area thus gained a new role as a creative park and tourist attraction, though many residents are demonstrably cool towards the weekend crowds, and have moreover found alternative uses for some of the artwork as chairs or even places to dry laundry.

While property-owning residents might financially benefit from the long-term revitalization of the area, the displacement of poorer residents by wealthier newcomers is of course never a total or complete process.2 What is striking is that what had occurred in Kaohsiung has all the outer marks of gentrification, with old shops closing and giving ways to design boutiques and artisanal coffee shops, followed by a 30% increase in real estate prices. And yet, this was a top-down initiative with clearly stated goals, an agreed timeline and due process in the city’s council. It was a project that relied from the outset on the collaboration of the city’s artist community, as well as the approval of the construction businesses, which were granted permissions to construct taller residential buildings in the area.

Gentrification by fiat, if you will.

What then about this example from one Asian marginal city is relevant to the rehabilitation of ‘gentrification’ as a useful term in describing the changes befalling Asian cities? Is it not simply a project of demolition, an Haussmannian echo of sorts? The simple answer is yes, that is precisely what it is, but within it lies the idea that art and creativity can and will change urban space, and beyond that, that they will change it in a way that accommodates ‘Soho-style living,’ as the city’s urban plan bluntly puts it. The legacy of a gentrifying New York or London does not necessarily live unchanged as an endless repetition of successive waves of real-estate price hikes and demographic changes. It manifests itself also in the ordered representations of space of the urban plan. But when aimed at working class neighbourhoods, it is (and always has been) a deproletarization of space; pausing on whether it is ‘planned’ (slum-clearance) or ‘organic’ (gentrification) is in many cases distracting from the point that the displacement typical of gentrification is not only the displacement of people, but in a Lefebvrian way, of the lived space of a neighbourhood for financial and political gain of established elites. To reiterate, the imposition of new conceptual space upon the city is not a natural or spontaneous process. Seeing such changes outside of the social and spatial context is not only incomplete, but also conservative in that it perpetuates neoclassical economists’ insistence on the emergent qualities of gentrification or slum-clearance, endowing urban restructuring with an air of unavoidable, organic change – precisely what Kaohsiung’s municipality tried to convey by consigning to history and artistic representation the living, clunking workshops of its waterfront.

Going back to gentrification as function of development, I suggest the baggage with which the term is burdened is what gives it the critical punch needed to make sense of the spatial transformations in Asian cities, where expectations of development clearly exhibit a tendency to create both the disinvestment needed to create ‘gentrifiable’ areas, as well as a pool of gentrifiers. While the debate between production-side and consumption-side explanations of gentrification thankfully no longer rages, we will be well served to remember that both explanations agree that gentrification as a phenomenon is essentially conditioned by a late-capitalist system. In China especially, where a retreating state has left municipal authorities dependent on land-dealing and thus with a clear interest in rising (or raising) land values, a race towards ever greater exploitation of urban space may manifest itself as either commercialization, gentrification or simply urban development, all of which are apparent not only in the physical space, but in the abstract, conceived space which seeks to impose itself on the city. Viewed in this light, the opening of a café or gallery may not be as serious a sign of gentrification as the commitment of district chiefs to pursue creative policies, though how far the market-driven side will progress remains to be seen. In Kaohsiung certainly, gentrification by culture remains a tool in the arsenal of urban policy.

1) Miller and Rose’s “Governing the Present” (2008) is a great look at the questions of governmentality in advanced liberal democracies, though many nuances equally apply to non-democratic states in advanced stages of development. �

2) While the displacement of working class residents with middle class newcomers is the usual hallmark of gentrification, I reject notions that this substitution must be complete. Vast stretches of London’s Hackney or Islington still remain predominately working class, while in other cases, such as on Broadway Market in Hackney, the mainly Turkish immigrant landlords have benefitted from rising commercial rents. Despite this, both areas remain clear-cut cases of gentrification.

Igor Rogelja is a PhD candidate at the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London. His research is focused on the role of creative city theory and art in urban redevelopment in Taiwan and China.

时间 posted on: 14 December 2020 |

时间 posted on: 14 December 2020 |  发布者 author:

发布者 author:

分类 filed under:

分类 filed under: