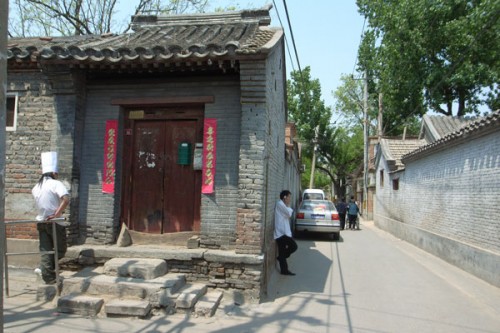

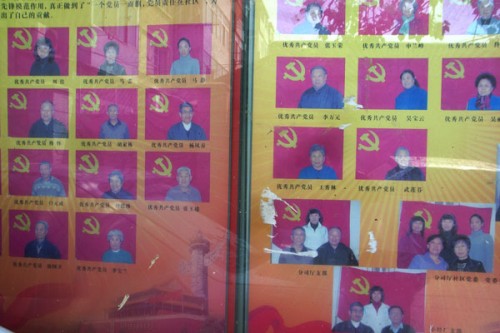

After a prolonged research and analysis period highly implicated by HomeShop’s recent search for a new space, our newfound expertise has led to the temporary return of the current space at Xiaojingchang hutong to its former status as real estate agency (pre-2007 era). We are pleased to inform you that we are taking up a new role as an offshoot office of the well-known chain 我爱我家 Wo Ai Wo Jia (“I Love My Home”), henceforth named 我爱你家 Wo Ai Ni Jia (“I Love Your Home”). If you are looking for a new house or office within Beijing’s old city centre or are merely interested to learn more about the real estate market and private life in the capital, our multilingual agents can offer free advice and direction regarding a selection of some of Beijing’s hottest properties. We do not take commission, and while our services may be limited, our knowledge is vast. Please stop by HomeShop or telephone to make an appointment. You may reach us at any time by mobile phone at 137 1855 6089.

Thank you! We are here waiting for your trust!

—–

“我爱你家 I Love Your Home” is a project of 何颖雅 Elaine W. HO and Fotini LAZARIDOU-HATZIGOGA for HomeShop. On view from 24 May 2010.

经过家作坊对寻找新空间的一段旷日持久地研究和分析,我们现在在小经厂胡同的空间暂时回到了它过去的房产中介公司状态(2007年早期)。我们很高兴的通知您,我们现在成为了著名连锁机构“我爱我家”的分店之一,并从此叫做“我爱你家”。如果您正在北京老城区的中心地带寻找房子或者办公室,或者至少对首都房地产市场和个人生活感兴趣的话,我们多语言的服务团队将为您提供免费咨询以及对某些北京最热房产的指南。我们不收取中介费,虽然服务项目有限,但我们的知识很丰富。请在家作坊门前留步,或电话预约。您可以在任何时间通过这个手机号码找到我们:13718556089。

谢谢!我们期待您的信任!

——

“我爱你家 I Love Your Home” 是由何颖雅 Elaine W. HO 及 Fotini LAZARIDOU-HATZIGOGA为家作坊做的一个项目。从2010年5月24日开始。

时间 posted on: 25 May 2010 |

时间 posted on: 25 May 2010 |  发布者 author:

发布者 author:

分类 filed under:

分类 filed under:

北京的第二场雪后的

北京的第二场雪后的

修车师傅宋贤根穿着蓝色工服干活 [photo by 杨弘迅 Winson Yang]

修车师傅宋贤根穿着蓝色工服干活 [photo by 杨弘迅 Winson Yang]