Songs of the Donkey

The reading club meeting, involving three texts somewhat innocent of each other’s connections, was held in the shop in Caochangdi. The texts—”The Burdens of Linearity: Donkey Urbanism” by Catherine Ingraham (1999), “Lethal Theory” by Eyal Weizman (2006) and “The Shanghai Gang” by Richard MacGregor (2010)—encompassed a broad range of issues whose relations could potentially crisscross and veer in various directions, for and against the grain of theory, out of or in the range of empirical topic. These texts were all further intertwined by their being chosen within the frame of the Donkey Institute of Contemporary Art’s Co-Director Michael Yuen, inviting speculation on applied theory or grounded discussion.

Within the sequence, the first text to be discussed was Weizman’s, which happened to be about the use of theory by the Israeli military in dealing with or rather in “interpreting” architecture, in their raids on Palestinian towns and settlements. The discussion led us from the “radical” technique of walking through walls, which is done by creating holes in existing architecture to make new paths through private spaces, and the supposedly non-hierarchical swarming techniques by which individual Israeli soldiers carry out their tasks independently and in no particular order, to tactical specificity (targeting particular individuals for capture or assassination), all ostensibly based on ideas derived from theorists such as Foucault, Deleuze and Tschumi. But that is not to say these techniques or theories, though they explain the complexity of contemporary built environments, populations and conflicts, are any less traumatic or destructive than conventional warfare. Consider the upending of the categories of private and public, which, after seeming like a novel shift in print, is utterly destabilizing when your house becomes a thoroughfare. We talked about how implicated theory itself was in this outcome, and whether such outcomes mandated changes in the way theory would be written.

Meanwhile Michael had to run outside because the donkey was getting some grief from one of the caretakers at the gate for trying to enter the brick art district. DICA had arrived, but for the moment, we pressed on with the texts.

Ingraham’s article counterposed a number of texts to draw out the subject of the beast in Modern architecture’s scheme of things. Beginning with Le Corbusier, who ridiculed the distractedness of the donkey vis à vis the straight intentional lines of Modern man and his cities; and continuing with Claude Lévi-Strauss’ description of getting lost on his mule in the jungle, which in the end becomes a revelation of his views of the relationship between writing systems, architecture, human organization and therefore mass violence; Ingraham’s account thereby leads its winding way to Jacques Derrida and to the subject of writing. To the ideas of the “origins” of straight lines and their import for urbanism. Ingraham says: “Urbanism and architecture, as we have already seen through the strange narratives of Le Corbusier and Lévi-Strauss, come (in a state of considerable hegemony) to the geometric (straight) line in the immediate presence of the animal (swerving, making a path), which irrevocably perturbs the hegemonic and the straight. And, lest we forget, the animal is not “The Animal,” but the principle of animality that belongs entirely to human culture.”

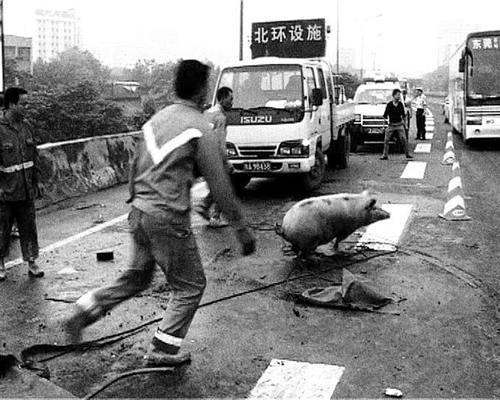

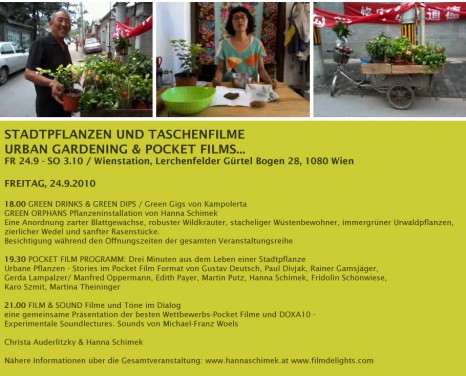

We took a group trip to the roadside display of books currently on view in DICA. A small crowd had gathered even on this side street, but this is the curious custom of the institute. The books were all translated with post-it notes, but there was one Chinese reader with his shirt off slowly, systematically orating aloud the English captions of David Shrigley’s red book. Someone stroked the animal’s muzzle (in fact, it looked like a bit like a horse). It’s interesting to see DICA at rest, because it is one of the rare moments when an institution can be seen to be loitering, waiting for the next thing, to move on, the cart owners squatting in the hot sun.

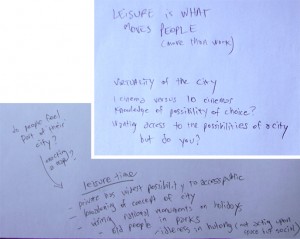

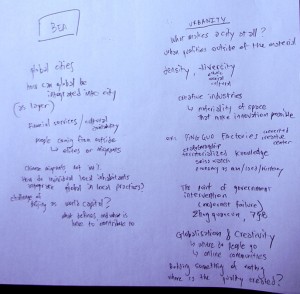

Finally, returning to the air-conditioned interior, we discussed the urban state of Beijing. To some degree the straight lines of Beijing were already unstraight from the beginning based on behavior like opposing traffic, bringing the intimate to the sidewalk; and the city’s fabric was already porous, plurally interpreted, multipurpose, because of the means and necessities of daily life, in the spaces of difference between the so-called privileged and underprivileged and the state and reality, most poignantly felt in the reducing to rubble of communities and erection of new developments within no time at all. And history. And some are happy, others angry, some come up with entrepreneurial solutions and some flee and some bear brunts. And yet as far as those people in the reading club meeting were aware, there is not much theory to support these observations, to reflect on the new perceptual and cognitive spaces that make up contemporary reality from this point of view. Not even co-opted theory. The last text was a chapter from Richard McGregor’s book about the inside of the Communist Party, a not-so-well understood organization. This chapter by McGregor, a financial journalist in his day-job, concerned the anti-corruption campaigns that targeted Shanghai’s dizzy urban developers and their government friends, marking the period of politcal turnover from Jiang Zemin to Hu Jintao, while it also demonstrated the difficulties facing anyone on a lower level trying to expose corruption using official bureaucratic channels. The philosophy behind this situation is challenging, because it is often not outwardly debated or addressed; but looking around at the cityscape, the effects of this hidden philosophy—visible at least in deed beneath the bold slogans—certainly seemed materially manifest. Perhaps the theory of the donkey can only be just such a blunt confrontation of material, and the reading group’s radar could simply not pick it up. When one person present, who was a local, was asked what happened to the people who get displaced when the buildings come down, he said he didn’t know.

时间 posted on: 16 September 2010 |

时间 posted on: 16 September 2010 |  发布者 author:

发布者 author:

分类 filed under:

分类 filed under: